Genes determine our eye color, height, development throughout life and even our behavior. All living beings have a set of genes that, when expressed, manifest themselves in a more or less explicit way in their body, modeling it and giving it a wide diversity of traits and functions. However, is it possible that the expression of some genes has effects beyond the body itself?

Discover some basic ideas about the extended phenotype theory.

The extended phenotype: genetics beyond the body

First of all, let’s talk about two basic, but not less important, concepts that will help you to understand the extended phenotype theory: genotype and phenotype.

Genotype

Genotype is the collection of genes or the genetic information that a particular organism possesses in the form of DNA. It can also refer to the two alleles of a gene (or alternative forms of a gene) inherited by an organism from its parents, one per parent.

It should not be confused with the genome: the genome is the set of genes conforming the DNA that a species has without considering its diversity (polymorphisms) among individuals, whereas the genotype does contemplate these variations. For example: the human genome (of the whole species Homo sapiens sapiens) and the genotype of a single person (the collection or set of genes and their variations in an individual).

Phenotype

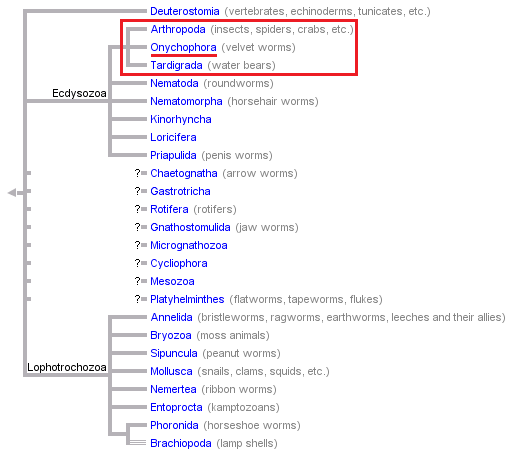

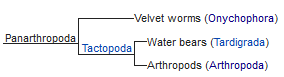

The genotype, or at least a part of it, expresses inside an organism thus contributing to its observable traits. This expression takes place when the information encoded in the DNA traduces to synthetize proteins or RNA molecules, the precursor to proteins. The set of observable traits expressed in an organism through the expression of its genotype is called phenotype.

However, genes are not always everything when defining the characteristics of an organism: the environment can also influence its expression. Thus, a more complete definition of phenotype would be the set of attributes that are manifested in an organism as the sum of its genes and the environmental pressures. Some genes only express a specific phenotype given certain environmental conditions.

The extended phenotype theory

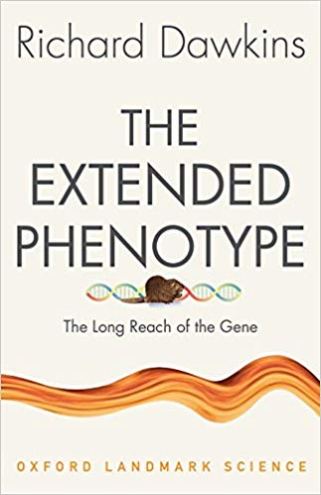

The concept of extended phenotype was coined by Richard Dawkins in his book “The Extended Phenotype” (1982). Dawkins became famous after the publication of what would be his most controversial work, “The Selfish Gene” (1976), which was a precursor to his theory of the extended phenotype.

In the words of Dawkins himself, an extended phenotype is one that is not limited to the individual body in which a gene is housed; that is, it includes “all the effects that a gene causes on the world.” Thus, a gene can influence the environment in which an organism lives through the behavior of that organism.

Dawkins also considers that a phenotype that goes beyond the organism itself could influence the behavior of other organisms around it, thus benefiting all of them or only one… and not necessarily the organism that expresses the phenotype. This would lead to strange a priori scenarios such as, for example, that the phenotype of an organism was advantageous for a parasite which afflicts it rather than for itself. This idea is summed up in what Dawkins calls the ‘Central Theorem of the Extended Phenotype’: ‘An animal’s behaviour tends to maximize the survival of the genes ‘for’ that behaviour, whether or not those genes happen to be in the body of the particular animal performing it’.

A complex idea, isn’t it? However, it makes sense if we take into account the basic premise from which Dawkins starts, which addresses in his work ‘The selfish gene’: the basic units of evolution and the only elements on which natural selection acts, beyond individuals and populations, are genes. So, organisms’ bodies are mere ‘survival machines’ improved to ensure the perpetuation of genes.

Examples of extended phenotype

Perhaps all these concepts seem very complicated, but you will understand them better with some examples. According to Dawkins, there exist three main types of extended phenotype.

1) Animal architecture

Beavers build dams and modify their surroundings, in the same way that a termite colony builds a termite mound and alters the land as part of their way of life.

On the other hand, protective cases that caddisflies build around them from material available in the environment improve their survival.

These are all examples of the simplest type of extended phenotype: the animal architecture. The phenotype is, in this case, a physical or material expression of the animal’s behavior that improves the survival of the genes that express this behavior.

2) Parasite manipulation of host behavior

In this type of extended phenotype, the parasite expresses genes that control the behavior of its host. In other words, the parasite genotype manipulates the phenotype (in this case, the behavior) of the host.

A classic example is that of crickets being controlled by nematomorphs or gordiaceae, a group of parasitoid ‘worms’ commonly known as hair worms, as explained in this video:

To sum up: larvae of hair worms develop inside aquatic hosts, such as larvae of mayflies. Once mayflies undergoe metamorphosis and reach adulthood, they fly to dry land, where they die; and it is at this point that crickets enter the scene: an adult cricket feeds on the remains of mayflies and acquires the hair worm larvae, which develop inside the cricket by feeding on its body fat. Adult worms must return to the aquatic environment to complete their life cycle, so they will control the cricket’s brain to ‘force’ it to find a water source and drop in. Once in the water, the worms leave the body of the cricket behind, which drowns.

Other examples: female mosquitoes carrying the protozoan that causes malaria (Plasmodium), which makes female mosquitoes (Anopheles) to feel more attracted to human breath than uninfected ones, and gall induced by several insects on different host plants, such as cynipids (microwasps).

3) Action at a distance

A recurring example of this type of extended phenotype is the manipulation of the host’s behavior by cuckoo chicks (group of birds of the Cuculidae family). Many species of cuckoo, such as the common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus), lay their eggs in the nests of other birds for them to raise in their place; also, cuckoo chicks beat off the competition by getting rid of the eggs of the other species.

Look how the cuckoo chick gets rid of the eggs of reed warbler (Acrocephalus scirpaceus)!

In this case of parasitism, the chick is not physically associated with the host but, nevertheless, influences the expression of its behavioral phenotype.

. . .

There are more examples and studies about this concept. If you are very interested in the subject, I strongly recommend you to read ‘The selfish gene’ (always critical and from an open minded perspective). Furthermore, if you have good notions of biology, I encourage you to read ‘The extended phenotype’.

Main picture: Alandmanson/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)