In October 2015 the world knew, late and wrong, about what would be later classified as the s. XXI biggest ecological crisis. Tropical rainforests and peatland forests of Southeast Asia in Indonesia burned for five long months causing the burn of two million hectares increasing the level of pollutant particles in the air up to 2,000 PSI (levels of more than 300 PSI are considered toxic). Forty-three million people were affected, 500,000 of them suffering respiratory diseases. The biodiversity of this region has been seriously compromised, affecting many endemic and endangered species, including one of the most emblematic and vulnerable primates in the world: orangutans; which only live on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo (Indonesia) of the most affected by the fires.

Because of this environmental crisis, we wanted to talk to Joana Aragay Soler, a biologist currently working in Kalimantan (the Indonesian part of Borneo) with the British NGO OuTrop (The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project) to explain us what does she do in the association and also concerned by the terrible experience she lives in the summer of 2015. Through some questions we want to understand how did she lived that crisis in first person and get deeper into the reasons that provoked the fires and their ecological and social consequences.

- Hi Joana! How are you? From AYNIB (All You Need Is Biology), we think that your experience as a biologist at OuTrop can be of great interest to our readers. What is your job in the NGO?

Hello, thank you very much for giving me the opportunity to share with you my experience in Borneo.I have two very different roles in OuTrop, but complementary at the same time. That makes my job very diverse and enriching. On the one hand, I am Head of the Biodiversity program (Biodiversity Scientist) and on the other I coordinate the Education program (Education Manager). As a Biodiversity scientist, I coordinate the fieldwork of all biodiversity research projects (other than primates). Outrop research began in 1999 monitoring only the orangutan populations and studying their behavior. A few years later, we began to establish the gibbons and red langurs project. Finally, the arrival of new researchers promoted the development of other projects, such as butterflies, ants, birds, frogs or spiders sampling in order to monitor the status of the forest through quality indicators species. Also we have a project with trap cameras with a motion sensor that allows monitoring elusive spices such as bears or clouded leopards.As the Education manager, I am developing the education project that has just started this year as we believe that a very important part to make conservation is education. For now, we have started to conduct environmental education in schools, but we also have an education project for non-solarized children, which consists on teaching them to read, write, etc., through of nature-related activities.

Finally, we also invite local and international schools to spend a few days in the jungle to experience firsthand how scientists work.

- How is your routine work in Borneo ?

My daily routine is very different depending on the project. When I am coordinating the biodiversity projects, I live in the camp OuTrop has in the jungle. Every day in the jungle is different, even when walking through the same transects, you never know what you’ll find: termites eating orangutans, bears perched on trees, oddly shaped insects or acrobats like gibbons swinging above your head.

When working at the education project I am in the city office in Palangkaraya. There I meet Riethma, an Indonesian girl also part of the education team. With this program the activities, visit schools and conduct workshops for children out of school. When I’m in town I also took time to catch up with the email because we don’t have internet access in the jungle.

- What experience from your work as a biologist would you highlight?

There are many exciting aspects of my job and even more when you work immersed in a culture different from yours. Living surrounded by jungle and being constant contact with nature is a privilege, especially in the area of Borneo where we work. Sabangau, is the largest south of Borneo rainforest and contains the largest orangutan population in the world (about 7,000 individuals). Investigating the biodiversity of these forests and working with local people to protect these habitats is very professionally satisfying.

- Now that we can imagine your routine, we would love you to share with us your vision of the fire of 2015. How you lived on a professional and personal level?

First of all let’s get in situation. From June to October 2015, more than 125,000 fires broke out in Indonesia burning more than two million hectares (which would represent 2/3 of the Catalonia surface or three million football fields). Kalimantan, the Indonesian part of Borneo suffered the worst effects, at all levels: ecological, economic and social. There was so much smoke that some days he saw nothing more than 20 meters away. Fires and the effects of the smoke affected everything: the airport, shops and schools closed during several weeks; agriculture losses were enormous; thousands of people have had or will have health problems in the medium or long term; ecological damage is of unimaginable dimensions and still needs to be evaluated. The fires emitted 1.6 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere (equivalent to the Spain, Germany, United Kingdom and France together annual carbon emissions sum), substantially contributing to climate change.

Those were difficult and emotionally intense months. Many research projects of the NGO were reduced to a minimum in order to devote every effort to firefighting.Personally, I decided to leave Kalimantan during a few days because I felt that my health was compromised. I spent the days conducting divulgation, awareness and seeking fundraising to subsidize equipment for firefighting. Thanks to the collaboration of many people and organizations we were able to buy a lot of stuff: water pumps, hoses, masks, etc. that we deliver to different firefighting teams and communities. We also try to visualize the problem, contacting media to give impact to the problem.

- Were those arson or natural fires? Which were the causes?

The fires were arson. Most started to thin out land and associated with the economic development of the region for requalify land to plant monocultures (mainly palm oil). During the dry season there are usually many fires but this year, due to El Niño, they were intensified. It’s a combination of factors, there’s not a single reason that explains the problem. We have to look back to understand the complexity of the problem and the vulnerability of ecosystems. Over the past 20 years, in the lowlands of Borneo thousands of channels were built, both for timber production and the agriculture development. Normally, tropical peatlands do not burn because they are like sponges that hold moisture but the channels disturbed the natural hydrology of tropical peatlands, draining the water into the rivers and disturbing the natural water levels on the ground; which caused the augmentation of fire risk.

Another structural problem is the lack of resources to fight the fires, there were so many that fire men were overwhelmed, and didn’t have the necessary resources to put them off.

- What were the ecological consequences?

The ecological consequences were terrible and will take years to quantify: it was estimated that nearly a million hectares of forest were lost and consequently the species that inhabit it. The fire increased pressure on primary forests and endangered species such as orangutans. The fire also burned forest areas where the greatest orangutan populations remain, and these are expected to experience a substantial decrease in the coming years.

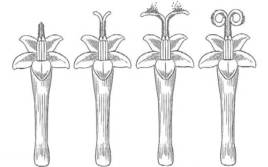

The peatland forests, though little known, are one of the most important ecosystems in the planet. They represent only 3% of the world forest area, acting as carbon reservoirs as they contain a third of the world carbon, and playing an important role in preventing global warming. Its biodiversity is huge and contains several iconic and endangered species such as the Southern Borneo gibbon, orangutans, clouded leopards or Storm’s storks.

- What about the social consequences? How did the fires affected the Borneo people?

One of the most immediate effects suffered was due to smoke. During September and October it was recommended to wear charcoal filtered masks 24 hours a day, but these masks were only found in some local within big cities and were very expensive. Most people wore only paper masks that were not able to filter smoke particles, they only minimized the risk perception. Many people got sick and the health consequences in the long term are unpredictable. Indonesia will have to face economic losses of about 30 billion dollars.

The loss of environmental resources is implicitly linked to the local economy. Many communities depend on the services that ecosystems provide. If the forest disappears resources that keep many families are also put at risk.

- Why do you think foreign media reacted so late?

The international media reacted slowly and the truth is that the Spanish and Catalan hardly mentioned the problem. From OuTrop, we send press releases and some were published, but the media exceptionally reports environmental issues and when they do it is always secondarily. Day after day we read irrelevant news published in national newspapers, while in Indonesia we were living one of the most important ecological and social crisis of recent decades. We cannot ignore that the media reports on what “sells” and not on what is really happening.

- How could we prevent this disaster never happen again?

Legislation and land management are key elements to prevent that forest areas are easily converted into farmland items. The hydrology of disturbed areas should also have to be restored. Population awareness, sustainable development and especially informing and educating people are basic to understand that the use of the slash and burn method is very dangerous and harmful to everybody.

- Now that you have returned a few months ago the rains, do you think that the environment can recover? Were you able to go to the countryside to meet the affected area?

Now that the fires are extinguished we have begun monitoring the primates populations and mapping the burned area. We don’t know how the fire consequences as it will take years to manifest. In OuTrop we are developing research projects associated with burned areas, that will provide answers in the future; patience is the mother of science, they say.

We have also stepped up efforts in reforestation programs, starting to replant trees in burned areas. We are doing various experiments to discover the best way to accelerate forest regeneration in these areas.

But most of all we hope that this experience has make people react and disasters like this won’t be repeated. Prevention is the best answer, but … we must be prepared!

Well Joana, thank you very much for sharing this experience and helping us to understand the origins of the Southeast Asia fires phenomenon. Hopefully your work, along with others foundations working there, will prevent the reoccurrence of disasters like this and that the population is increasingly aware of the effects of burning forest.

Joana leaves us some links with photos and a documentary for those who want to go in depth into the subject:

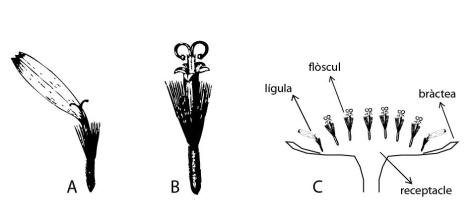

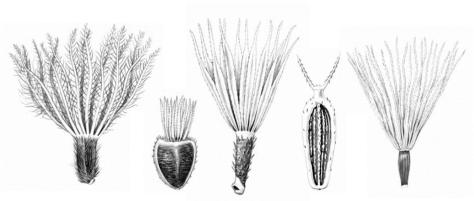

botànica per la Universitat de Barcelona. Vaig estudiar la meva tesis doctoral a l’Institut Botànic de Barcelona (CSIC –ICUB), que es va centrar en entendre l’evolució i biogeografia de dos grups de plantes molt diferents, les Euphorbia arbustives macaronèsiques conegudes com a tabaibes i la subtribu de les Cardueae (Asteraceae). Llicenciada en biologia i màster en biodiversitat també per la Universitat de Barcelona. Professionalitzada en educació i divulgació científica i per a la sostenibilitat, he treballat en diverses empreses d’educació ambiental i museus de ciències.

botànica per la Universitat de Barcelona. Vaig estudiar la meva tesis doctoral a l’Institut Botànic de Barcelona (CSIC –ICUB), que es va centrar en entendre l’evolució i biogeografia de dos grups de plantes molt diferents, les Euphorbia arbustives macaronèsiques conegudes com a tabaibes i la subtribu de les Cardueae (Asteraceae). Llicenciada en biologia i màster en biodiversitat també per la Universitat de Barcelona. Professionalitzada en educació i divulgació científica i per a la sostenibilitat, he treballat en diverses empreses d’educació ambiental i museus de ciències.