There’s a reptile in New Zealand whose lineage arose in the time of the dinosaurs. Even if its external appearance is similar to that of a lizard, the tuatara (whose name means “spiny back” in the Maori language) is an animal with many unique characteristics that classify it in an order different from the other reptiles. In this entry we’ll explain the main characteristics of this relic from the past, as interesting as endangered.

ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION

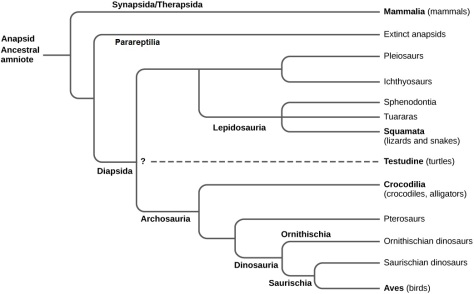

The tuataras are unusual reptiles whose lineage goes back to 240 million years ago, at the middle Triassic. Tuataras are lepidosaurs, yet they form a different lineage from the squamates, and that’s why they are found in their own order, the rhynchocephalians (order Rhynchocephalia). Lots of species flourished during the Mesozoic, even if almost all of them were replaced by squamates. At the end of the Mesozoic only one family survived, the Sphenodontidae.

Of all the existing sphenodontids, only tuataras have survived to the present day. Traditionally it was considered that tuataras included two species: the common tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) and the Brother’s Island tuatara (Sphenodon guntheri), although recent analyses have popularized the idea that the tuatara is only one species, S. punctatus.

TUATARA ANATOMY

As we have already stated, tuataras look externally like a lizard, having a certain resemblance to iguanas. Male tuataras are larger than females, measuring up to 61 cm in length and one kilogramme of weight, while females only measure 45 cm and weigh half a kilo. Tuataras present a spiny crest on their backs which give them their common name. This crest is bigger in males, and can be erected as display.

What really distinguishes the tuataras is their internal anatomy. All the other reptiles have modified greatly their skull structure, but tuataras have maintained the original diapsid configuration without most changes. While crocodiles and turtles have developed a sturdy skull, tuataras conserve wide temporal openings, and while squamates have developed flexible skulls and jaws, tuataras keep a rigid cranium. Also, unlike most reptiles, tuataras present no external ears.

The name Rhynchocephalia means “beak head” and it refers to the beak-like structure of their premaxilla. Tuataras are also one of the few reptiles with acrodont teeth, which are fused to the maxilla and the jaw, and are not renewed. Also, they present a unique saw-like jaw movement, moving it forwards and backwards.

Video by YouOriginal, of some captive tuataras feeding. In this video we can appreciate the singular jaw movement.

Finally, one of the more incredible anatomic characteristics of tuataras is that they conserve their parietal or pineal eye. This is a structure reminiscent from the first tetrapods, which connects with the pineal gland and which is involved in the thermoregulation and circadian rhythms. Even if some other animals also keep it, the tuataras present a real third eye, with complete lens, cornea and retina, even if it gets covered with scales as they age.

HABITAT AND BIOLOGY

Tuataras live in some thirty islets in the Cook Strait, between the two main islands of New Zealand. Also, the previously considered species S. guntheri is found on Brother’s Island, in the northwest of South Island. All populations live in coastal forests or scrublands, with loose soils easy to dig. Also, in most of their distribution area there are colonies of sea birds, whose nests are also used by tuataras.

Compared with most reptiles, tuataras live in relatively cold habitats, with annual temperatures oscillating between 5 to 28°C. Tuataras are mainly nocturnal, usually coming out of their burrows at night, even if sometimes they can be found basking in the sun during the day (especially in winter).

Tuataras have few natural predators. Apart from some introduced animals, only gulls and some birds of prey represent a danger for these reptiles. In contrast, their diet is fairly varied. Being sit-and-wait predators, tuataras feed mainly on invertebrates like beetles, crickets and spiders, even if they are able to predate on lizards, eggs and bird chicks, and even younger tuataras. As their acrodont teeth don’t renew, these get worn down in time, so older individuals usually feed on softer prey like snails and worms.

Tuataras mate between January and March (summer), when the territorial males compete for the females, which will lay around 18-19 eggs between October and December (spring). The sex of the offspring depends on the incubation temperature (males at higher temperatures and females at lower ones). The eggs will hatch after 11-16 months (one of the longest incubation periods of all reptiles), from which young tuataras will be born, who will avoid the cannibalistic adults being active mainly during the day.

Unique video of the birth of a tuatara at the Victoria University of Wellington. The translucent mark on the little tuatara’s head corresponds to the parietal eye.

As we can see based on their long incubation period, tuataras develop slowly. These reptiles do not reach sexual maturity until the age of 12, and they keep growing. Also, tuataras are extremely long-lived animals, living up to more than 60 years in the wild. In captivity they can live more than 100 years.

CONSERVATION AND THREATS

Before the arrival of man, the tuataras were present in both main islands of New Zealand and many more islets. When the first European settlers arrived, tuataras were already only found in about 32 little islands. It’s believed that the extinction of tuataras from the main islands was due to habitat destruction and to the introduction of foreign mammals like rats. Other threats include the low genetic diversity caused by isolation of the different populations and climate change, which can affect the sex of the offspring.

When the first human settlers arrived in the isles, it is thought that 80% of New Zealand was covered in forests. When the first Polynesian tribes came around the year 1250, they caused the deforestation of more than half the archipelago. Centuries later, with the arrival of Europeans, deforestation intensified even more, up to the current situation, with only 23% of the original forest still preserved.

The introduction of foreign mammals has been one of the main factors of the recent decline of tuataras, especially the introduction of the Pacific rat (Rattus exulans). This rodent has affected the populations of both tuataras and many of New Zealand’s endemic bird species. In studies on coexisting populations of tuataras and rats, it has been observed that rats, apart from preying on eggs and hatchlings, also compete with adult tuataras for resources. With an extremely slow life cycle, tuataras can’t recover from this impact.

Yet, tuataras are currently classified as “least concern” in the IUCN red list. This is thanks to the great efforts of conservation groups that have contributed to the recovery of this species. One of the main tasks has been the eradication of the Pacific rat from the main island where tuataras live. In order to do that, a titanic effort was made in many islets where entire populations of tuataras were captured to participate in captive breeding programs, while the rats were eliminated from these islands. After their main threat was eradicated, all the captured individuals and their captive-born offspring were released in their natural habitat so they could live without such a fierce competitor.

Video by Carla Braun-Elwert, about the breeding success of an old tuatara couple.

Currently, the wild tuatara population is estimated to be between 60.000 and 100.000 individuals. It can be said that this living fossil, which was on the brink of extinction after millions of years of existence, received a second opportunity to keep inhabiting the incredible islands of New Zealand. We hope that in the future, we can keep enjoying the existence of these reptiles, the only survivors of a practically extinct lineage, for many more centuries.

REFERENCES

The following sources have been consulted during the elaboration of this entry:

- Halliday & Adler (2007). La gran enciclopedia de los Anfibios y Reptiles. Editorial Libsa.

- Arkive. Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus).

- The Reptile Database. Sphenodon punctatus.

- Department of Conservation, Te Papa Atawhai. Tuatara.

- Imagen de portada de Michal Klajban.

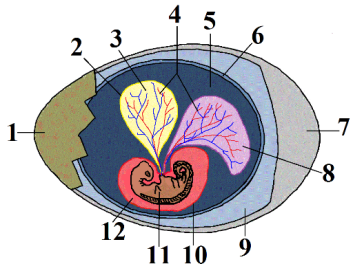

Diagram of a crocodile egg: 1. eggshell 2. yolk sac 3. yolk (nutrients) 4. vessels 5. amnion 6. chorion 7. air 8. alantois 9. albumin (white of the egg) 10. amniotic sac 11. embryo 12. amniotic fluid. Image by

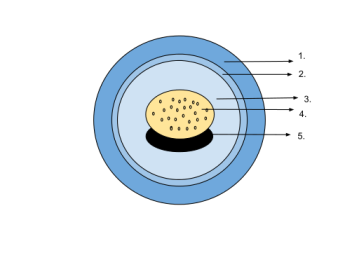

Diagram of a crocodile egg: 1. eggshell 2. yolk sac 3. yolk (nutrients) 4. vessels 5. amnion 6. chorion 7. air 8. alantois 9. albumin (white of the egg) 10. amniotic sac 11. embryo 12. amniotic fluid. Image by  Diagram of an amphibian egg: 1. jelly capsule 2. vitelline membrane 3. perivitelline fluid 4. yolk 5. embryo. Image by

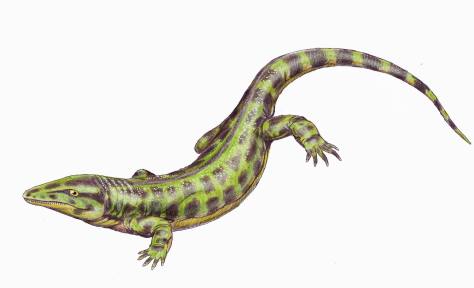

Diagram of an amphibian egg: 1. jelly capsule 2. vitelline membrane 3. perivitelline fluid 4. yolk 5. embryo. Image by  Reconstruction of Solenodonsaurus janenschi, one of the candidates in being the first amniote, which lived around 320-305 million years ago in what is now the Czech Republic. Reconstruction by

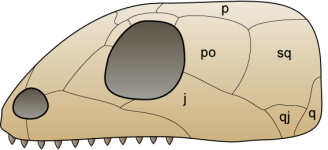

Reconstruction of Solenodonsaurus janenschi, one of the candidates in being the first amniote, which lived around 320-305 million years ago in what is now the Czech Republic. Reconstruction by  Diagram of an anapsid skull, by

Diagram of an anapsid skull, by  Diagram of a synapsid skull, by

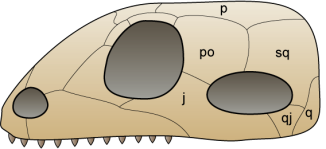

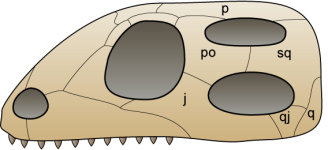

Diagram of a synapsid skull, by  Diagram of a diapsid skull, by

Diagram of a diapsid skull, by  Drawing of the skull of Archaeothyris, which is thougth to be one of the first synapsids that lived around 306 million years ago in Nova Scotia. Drawing by

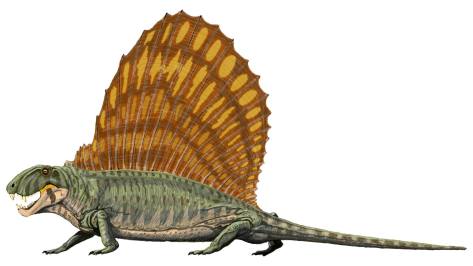

Drawing of the skull of Archaeothyris, which is thougth to be one of the first synapsids that lived around 306 million years ago in Nova Scotia. Drawing by  Reconstruction of Dimetrodon grandis, one of the better known synapsids, from about 280 million years ago. Reconstruction by

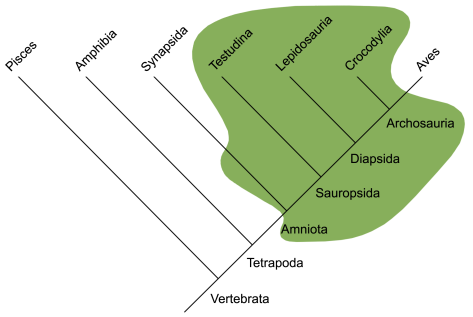

Reconstruction of Dimetrodon grandis, one of the better known synapsids, from about 280 million years ago. Reconstruction by  Evolutionary tree of current vertebrates, in which green color marks the groups previously included inside reptiles. As you can see, the traditional conception of "reptile" includes the ancestors of mammals and excludes birds. Image by

Evolutionary tree of current vertebrates, in which green color marks the groups previously included inside reptiles. As you can see, the traditional conception of "reptile" includes the ancestors of mammals and excludes birds. Image by  Shed skin of a rat snake. Photo by

Shed skin of a rat snake. Photo by  Photo of a tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), by

Photo of a tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), by  Photos of some squamates, from left to right and from top to bottom: Green iguana (Iguana iguana, by

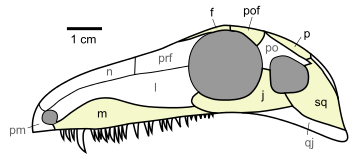

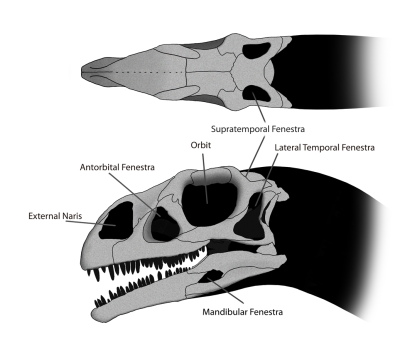

Photos of some squamates, from left to right and from top to bottom: Green iguana (Iguana iguana, by  Drawing of the skull of the dinosaur Massospondylus in which we can see the different characteristic openings of diapsid archosaurs. Image by

Drawing of the skull of the dinosaur Massospondylus in which we can see the different characteristic openings of diapsid archosaurs. Image by  Photo of two species of modern arcosaurs: a Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) and a yellow-billed stork (Mycteria ibis). Photo by

Photo of two species of modern arcosaurs: a Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) and a yellow-billed stork (Mycteria ibis). Photo by  Skeleton of the extinct tortoise Meiolania platyceps which lived in New Caledonia until 3000 years ago. In this photo it can be seen the compact cranium without openings. Photo by

Skeleton of the extinct tortoise Meiolania platyceps which lived in New Caledonia until 3000 years ago. In this photo it can be seen the compact cranium without openings. Photo by  Individual leopard tortoise (Stigmochelys pardalis) from Tanzania. Photo by

Individual leopard tortoise (Stigmochelys pardalis) from Tanzania. Photo by